Note: This is a loose transcript of a course for ESPR 2017, hence the colloquial/oral style.

Warm-up

- Look at several pieces of writing from this list.

- Answer these questions:

- What are features of “this kind of writing”?

- How would you go about writing “this kind of writing”?

Models of writing

Model 1

You might have a model of writing that looks something like this. You get an assignment from language class: write an essay about a certain topic. Then you sit down,

- think very hard to come up with some thoughts, and

- work really hard to write it all down, and

- it doesn’t look so good, so you dress it and make the sentences more eloquent.

Finally you finish and turn it in and don’t think about it until you get back your paper.

In summary, the model is

- You have an idea or purpose in your head.

- You write down the idea and dress it up.

This isn’t how most writing works (in the real world)!

Model 2

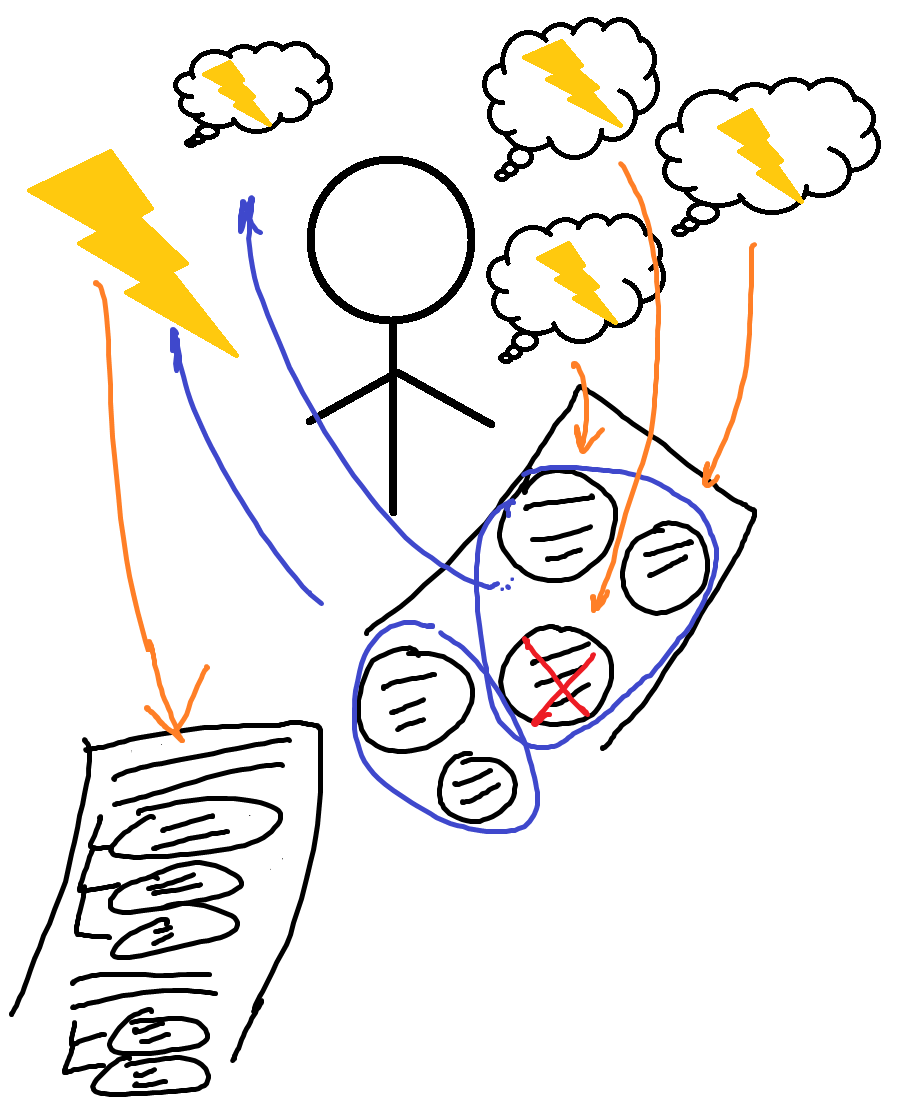

Here’s an alternate model of writing.

- You have a bit of an idea in your head.

- You write it down - it’s a small idea, so it’s just a sentence or two.

- Later, you have another idea.

- You write the idea down.

- After a while, you look at your writing, and because paper has more memory than your head, you see connections between ideas and they “glom” together into a larger idea. You see that some ideas are wrong, and replace them with correct ones. You have improved ideas in your head.

- You go back and forth between more accurate or beautiful thoughts, and clearer and more compelling writing.

- At the end, you have these clusters of ideas, and you want to tell other people about them. You arrange these ideas, adds some section headers and some connecting bits, and you’ve finished an essay, or maybe a book.

Comparison

Let’s compare the two models.

- In the previous model, you get an idea (no matter whether it’s good or bad), write it all out, and then try to make the writing good. Here, the process of building ideas and writing are tightly linked.

- In either model, writing takes work. But instead of being this big difficult thing, you can view writing as an incremental thing where work feels more spread out, where every step feels more natural and yummy.

Aside: English class

I want to put this in the perspective of English (or language arts) class. English class made me confused about writing. See The beauty of ideas vs the beauty of writing.

Writing isn’t just for academics. You can write the ideas that come to you in daily life.

How to have ideas

But I don’t have anything worth writing down!

Who writes posts on facebook? Or any words on social media?

You are writers (maybe not good, or long-form writers, but writers nonetheless). You have things that you want to tell your friends, stories or activities you want to share - you just don’t associate your thoughts with things that are written down, or the things that are written down with “writing” which may seem reserved for something serious and academic. And if you don’t think of your thoughts as worth recording, they can slip by and you can forget them.

I’ve had people tell me they’re not good at writing, but when I talk to them, I have a fascinating conversation about something they’re interested in - and if I just transcribed the interview, it might need some editing, but it would be a good piece of writing.

People often ask writers where they get their ideas from…

You get ideas from daydreaming. You get ideas from being bored. You get ideas all the time. The only difference between writers and other people is we notice when we’re doing it.

You get ideas when you ask yourself simple questions. The most important of the questions is just, What if…? …If only…

Index cards as pensieves

In the Harry Potter world, “pensieves” are these basins you can put your memories into, so that you can review them anytime later.

I think this is awesome - when there’s something that you keep thinking about, or want to reference later, wouldn’t it be great if you could just capture it and put it somewhere?

We don’t have pensieves, but we do have writing. When you write a thought down, you can rethink it anytime without fear of forgetting it, and build on it.

I like to think of index cards as pensieves. They don’t have to be literally index cards.

An index card is a natural size for writing. Imagine something you would write on an index card - like Trefethen’s index cards. An index card has the feature of not being too large - there’s not much space - and the feature of being a coherent idea (or cluster of ideas).

Some of the examples are from Lloyd Trefethen, who wrote a lot of his thoughts on 4x6 index cards and then published around 200 into a book.

When you have an idea “index-carded”, you can then hold a concept clearly in your mind and easily transmit it to others with good fidelity (and they can transmit it to yet more people). Something with the size and coherence of an index card is mimetic.

Here’s an index card on index cards.

System

In order for this model of writing to work, you need a notetaking system. I don’t mean a notetaking system in the restricted sense of taking down an hour-long lecture; I mean a system where you can easily write down your thoughts at any time.

The two criteria for such a system are:

- It has low activation energy.

- It is easily searchable.

You can use any notetaking framework. I recommend using workflowy or dynalist. You can use a wiki, blog, or journal for writing up longer posts. When you’re out and around and you have a good idea, you can write them down on your phone or pocket notebook.

Exercise

Come up with a list of things that you want to write about. Nothing is too small. Good search terms:

- Hobby, interest, topic, or activity you like, especially something that is less common.

- Things that you keep coming back to - things you want to pensieve.

- Personal philosophy - what’s a way you look at the world that’s unique to you?

- Thing that happened to you, that tickled you in some way.

- What do you want to communicate to people? If you could give everyone in the world (or your community) an index card, what would be on it?

- A book/movie/etc. you like. A person you admire. What are the key ideas or qualities?

- Things you like to tell other people in conversation

Note that Trefethen’s index cards are often about a thing that happens in daily life, plus a reflection on it. Also note how he can use an experience to define a whole category of experiences.

Now that we have ideas, how do we write them well?

How to write well

The inversion heuristic

There’s a lot of specific advice out there (see for example What I learned from Patrick Winston); I’ll just give one general principle, the inversion heuristic.

The inversion heuristic is: Put yourself in the reader’s shoes. What do they want? How can you make the writing compelling and useful to them?

Taking a coarse view, there are two things (nonfiction) writing needs to do.

- Say why the topic is interesting.

- Deliver the information so that the structure in your head becomes the structure in the reader’s head. For example, if you’re teaching someone an activity, give the the steps clearly. (Try to communicate the structure - if it’s a list, give a list. If it’s a dialogue in your head, give it as a dialogue - you aren’t constrained to a certain format, like you learn in English class. If a picture helps, draw it in.)1

This is very similar to teaching: imagine you were learning the material for the first time - what would you want?

- You want to know why you’d even care about the topic - why is it interesting?

- You want clear instructions on how to do the thing.

Note that many of the things that work to get better for writing or more generally communication for other people, also help even if you’re only making notes to yourself. For example, in order for your notes to help you remember your thoughts, you must write clearly; on the other hand, being concise means writing and reading doesn’t take up a lot of your time, or fill your head with irrelevant details.

One thing that you do have to do more of when writing to other people is to make a bridge - for example make them interested if they’re not already as interested as you are, and give them background they need to understand.

Exercise

- Choose one thing from your list, that you wanted to write about.

- Pair up.

- Interview your neighbor about their topic. Try to ask the questions so that YOU can write about it. Then write an outline. Don’t stop your line of questioning until you feel you see why their thing is interesting, and break it down into its parts.

The point of the exercise is: When you’re writing by yourself, you will be your own critic, imagining yourself as a reader who needs to be convinced and taught. That’s a skill to be developed, so here, you have someone else to be a critic.

You want your writing to be compelling, and the arguments to follow naturally. Writing your own ideas, you may miss something that you think is “obvious”, or assume the reader already thinks the material is interesting or conceptualizes it in a similar way as you. Or you may have cached an argument that you’ve heard and are just repeating it without thinking it through. Eventually, you want to be your own critic in terms of exposing these gaps. Finding these gaps is useful not just for communicating to others, it can help you realize there were gaps in your knowledge and improve your conception of the idea!

Conclusion

Moonwalking with Einstein

In Moonwalking with Einstein, the author talks about his journey of training for the International Memory Olympiad, and on the way, gives the history of writing and the history of memorization.

Before the printing press, having copies of manuscripts was costly. Learned people memorized entire books in their heads, so they could conjure up the knowledge they needed anytime.

In the modern age, memorization can seem obsolete, because the Internet gives instant information at our fingertips. Some people worry that this has dumbed us down.

Joshua Foer presents the following dilemma: In this age, we read a lot of books and articles - but how much of it do we actually remember? If we didn’t remember it, what was the point of reading it?

One answer to this dilemma is as follows. We don’t need to memorize everything, because we have information at our fingertips - but neither are we intelligent by having Internet access alone. We are overwhelmed by that raw information. Instead, we maintain a kind of superstructure of “notes” between us and all the information out there.2

I want to end with my conception of what being “well-read” is. It’s not sufficient to just read a bunch of books if you forget what you read. Read widely, and reflect, record, and summarize things that you read.3 Remember that they can be bite-sized. Index into books and articles.

Writing for all aspects of life

Writing notes down, organizing, and later reflecting or expanding them is a habit that’s useful in many areas of life, and that will have more gains the more you develop it.4

Here are some examples:

- How many of you have gone to a talk, and felt you didn’t get anything out of it? Here’s a suggestion: try to get three things out of a talk. If you can get three things out of a talk, it was a successful talk. Note that three things can fit on an index card.

- This isn’t just for “rational” stuff. Artists do it too. A painter might have post-it notes all over their easel.

- Write down concise articulation of what makes something good. I recommend the following exercise for creative writing: take some books you really like. Think about and write down what makes them interesting and different. (For example, for Lord of the Rings: It’s not a story about an ambitious person setting out to find treasure, but a story about a non-ambitious person (Hobbit) setting out to destroy treasure (the ring).)

- Creative writing: go back and forth between exploratory writing (unstructured) and outlining (structured). See here. Kazuo Ishiguro talks about “bottling up” in his interview.

- It’s useful to write down summaries/notes of many things, like conversations and people (Farley file).

- How do you remember a story for storytelling (or other oral presentation)? Imagine it as a scene (like a visual index card).

One thing to consider doing is to start a blog! I’m happy to help you set it up.

Take some index cards! Write things on them. Your mind is a net, capturing ideas as you move through the world…

There’s a table in the googledoc. I encourage you to post your “index cards” there. (You can also take a picture of your index card and upload it.)

Other references and links

- Nonfiction writing advice (Slatestarcodex): highly recommended

- Writing for thinking (Evan Chen).

- My (very abbreviated notes) on a CFAR alumni reunion class, Notetaking 101: Growing an exobrain (Joel Solymosi).

- What I learned from Patrick Winston.

Minsky does this, e.g. in The Emotion Machine. Here is one article I wrote as a conversation: Conversation on curiosity.↩

See Vannevar Bush’s conception of the memex in As we may think.↩

One warning: when you’ve written too much, it can be easy to get sucked into reviewing your writing. Forget your index cards↩