Sampling from multimodal distributions by raising the temperature

Rong Ge, Holden Lee, Andrej Risteski

Posted: 2018-11-08 , Modified: 2018-11-08

Tags: math

Parent:

Children:

Rong Ge, Holden Lee, Andrej Risteski

Posted: 2018-11-08 , Modified: 2018-11-08

Tags: math

Parent:

Children:

Many probability distributions that arise in practice are multimodal and hence challenging to sample from. One popular way to overcome this problem is to use temperature-based methods. In this post I describe work with Rong Ge and Andrej Risteski (in NIPS 2018) which gives rigorous guarantees for a temperature-based method called simulated tempering when applied to simple multimodal distributions. For more information, check out the paper, slides, talk transcript, and poster.

We address the following fundamental problem in theoretical computer science and Bayesian machine learning:

Sample from a probability distribution with density function \(p(x) = \frac{e^{-f(x)}}{\int_{\R^n} e^{-f(x)}\,dx}\), \(x\in \R^d\), given query access to \(f(x)\) and \(\nabla f(x)\).

In the case where \(f\) is convex (we say that the distribution \(p(x)\) is log-concave), a classical Markov chain called Langevin diffusion gives an efficient way to carry out the sampling. Log-concavity is sampling analogue of convexity, and Langevin diffusion is the analogue of gradient descent: it is gradient descent plus Gaussian noise.

However, just as most interesting optimization problems are non-convex and often have multiple local minima, most intersting sampling problems - such as those arising from deep generative models - are not log-concave, and often have multiple modes. We can’t hope to solve the problem in full generality, but we can hope to find methods that work for a wider class of distributions, including some multimodal distributions.

One general approach to sample from a probability distribution is to define a Markov chain with the desired distribution as its stationary distribution. This approach is called Markov chain Monte Carlo. However, in many practical problems, the Markov chain does not mix rapidly, and we obtain samples from only one part of the distribution.

Thus, our algorithm requires two ingredients:

We cannot use Langevin diffusion by itself because it is a Markov chain with local moves that gets stuck in a local mode.

Instead, we create a meta-Markov chain (the simulated tempering chain) which changes the temperature to exponentially speed up mixing. To raise the temperature of a distribution means to smooth it out so that the Markov chain can more easily traverse the space. While temperature-based methods have been used heuristically, strong guarantees for them have so far been lacking.

We show that our algorithm allows efficient sampling given a structural assumption on the distribution: that it is close to a mixture of gaussians (of equal covariance) with polynomially many components.

Our main theorem is the following.

Theorem: Let \(p(x)\propto e^{-f(x)}\) be a mixture of gaussians, i.e., \[f(x)=-\log\pa{\sumo in w_i e^{-\fc{\ve{x-\mu_j}^2}{2\si^2}}}.\] Suppose that \(\si, \ve{\mu_j}\le D\) and we can query \(f(x)\), \(\nb f(x)\). There is an algorithm (based on Langevin diffusion and simulated tempering), which runs in time \(\poly(1/w_{\min},1/\si^2,1/\ep,d,D)\) and samples from a distribution \(\wt p\) with \(\ve{p-\wt p}_1\le \ep\).

Moreover, this theorem is robust in the following sense: if \(p(x)\) is a factor of \(K\) away from a mixture of gaussians, then we incur an additional factor of \(\poly(K)\) in running time. The theorem also extends to a mixture of strongly log-concave distributions of the same shape; we discuss the gaussian case for simplicity.

The main technical ingredient is a theorem giving criteria under which a simulated tempering Markov chain mixes. This is not tied to Langevin diffusion, and can also be applied to Markov chains on other spaces.1

Below, I give some motivation for the problem, describe the algorithm that we use, and sketch the proof of the theorem.

The typical scenario of interest in machine learning is sampling from the posterior distribution over the parameters or latent variables in a Bayesian model. Examples include gaussian mixture models, topic models (latent Dirichlet allocation), stochastic block models, and restricted Boltzmann machines. Given a prior \(p(h)\) over the parameters or latent variables \(h\), and a model \(p(x|h)\) for how the observables \(x\) are generated from \(h\), we wish to calculate the posterior distribution of \(h\) after observing many data points \(x_1,\ldots, x_N\). The posterior distribution is given by Bayes’s Rule: \[p(h|x_1,\ldots, x_N) \propto p(x_1,\ldots, x_N|h)p(h).\]

Even for simple models, the posterior is multimodal. Consider the simple example of a mixture of \(m\) gaussians with unknown means \(\mu_j\) and unit variance, where each point is equally likely to be drawn from each cluster. Suppose we observe data points \(x_1,\ldots, x_N\). Then the posterior update \(p(x_1,\ldots, x_n|\mu_1,\ldots,\mu_j)\) is proportional to \(\prod_{n=1}^N \pa{\sumo jm \rc m \exp\pa{-\fc{\ve{x_n-\mu_j}^2}2}}\). This expands to a sum of exponentially many gaussians, which is multimodal in the \(\mu_j\).

The story for sampling parallels the story for optimization. In optimization, the problem is to find the minimum of a function \(f\). When \(f\) is convex, there is a unique local minimum, so that local search algorithms like gradient descent are efficient. When \(f\) is non-convex, gradient descent can get trapped in one of many local minima, and the problem is NP-hard in the worst case. However, gradient descent-like algorithms often still well in practice, suggesting that we can achieve better results by taking into account the structure of real-world problems.

Similarly, in sampling, when \(f\) is log-concave, the distribution is unimodal and a natural Markov chain called Langevin diffusion (which is gradient descent plus noise) mixes rapidly. When \(f\) is non-log-concave, Langevin diffusion can get trapped in one of many modes, and the problem is #P-hard in the worst case. However, sampling algorithms can still do well in practice, with the aid of heuristics such as temperature-based methods.

Modern sampling problems arising in machine learning are typically non-log-concave. Like in nonconvex optimization, we must go beyond worst case analysis, and find what kind of structure in non-log-concave distributions allows us to sample efficiently.

The main observation connecting optimization and sampling is that if we sample from \(e^{-f}\), we’re more likely to get points where \(f\) is small. Thus, sampling is useful even if one is only interested in optimization. Langevin dynamics has been used heuristically to explain the success of SGD, as an optimization algorithm to escape local minima, and has inspired entropy-SGD for optimizing neural networks. The idea of using randomness has also been used to escape from saddle points. One generic algorithm for online optimization is the multiplicative weights algorithm, which reduces to a sampling problem in the continuous case (Narayanan et al. 2010). Moreover, there are settings such as online logistic regression in which the only known way to achieve optimal regret is through a Bayesian sampling approach.

Break here if splitting into two posts. In the next post I describe our algorithm and give a sketch of the main proof. / Continuing the previous post, I now describe our algorithm to sample from multimodal distributions \(p(x)\propto e^{-f(x)}\), given query access to \(f\) and \(\nabla f\).

The two components of our algorithm, Langevin diffusion and simulated tempering.

Langevin diffusion is a continuous time random-walk for sampling from \(p\propto e^{-f}\), given access to the gradient of the log-pdf, \(f\). It is gradient flow plus Brownian motion, and described by a stochastic differential equation \[dx_t = -\be_t \nb f(x_t)dt + \sqrt 2 d W_t.\] The \(\eta\)-discretized version is where we take a gradient step, with step size \(\eta\), and add gaussian noise scaled by \(\sqrt{2\eta}\):2 \[x_{t+\eta}=x_t-\eta \nb f(x_t) + \sqrt{2\eta}\xi_t.\]

Langevin diffusion has been well-studied, both in the math and CS communities. It is a classical result that the stationary distribution is proportional to \(e^{-f(x)}\). Bakry and Emery showed in the 80’s that if \(p\) is \(\alpha\)-log-concave, then the mixing time is on the order of \(\frac 1{\alpha}\) (see Terence Tao’s blog post).

With the recent algorithmic interest in Langevin diffusion, we want similar guarantees for discretized chain - that it converges to a measure close to \(p\). This was done in a series of works including Dalalyan et al. 2017, Durmus et al. 2018, and Bubeck et al. 2015 who also considered restriction to a convex set. For general distributions \(p\) with some regularity conditions, Raginsky et al. 2017 showede convergence to \(p\) in time comparable to continuous dynamics.

So why can’t we just run Langevin diffusion?

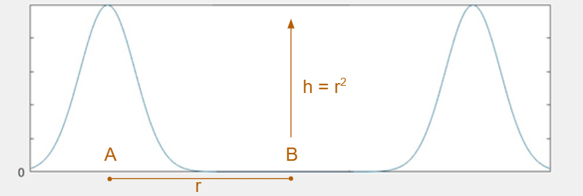

Consider the example of well-separated gaussians. Bovier et al. 2004 showed, via the theory of metastable processes, that transitioning from one peak to another takes exponential time. Roughly speaking, to estimate the expected time to travel from one mode to the other, consider paths between those modes. The time will be inversely proportional to the maximum, over all paths between the modes, of the minimum probability on the path.

If two gaussians with unit variance have means separated by \(2r\), then any path between them will pass through a point with probability less than \(e^{-r^2/2}\), so it will take on the order of \(e^{r^2/2}\) time to move between the gaussians. Think of this as a “energy barrier” Langevin diffusion has to cross. Even if \(r\) is as small as \(\log d\), the time will be superpolynomial in \(d\).

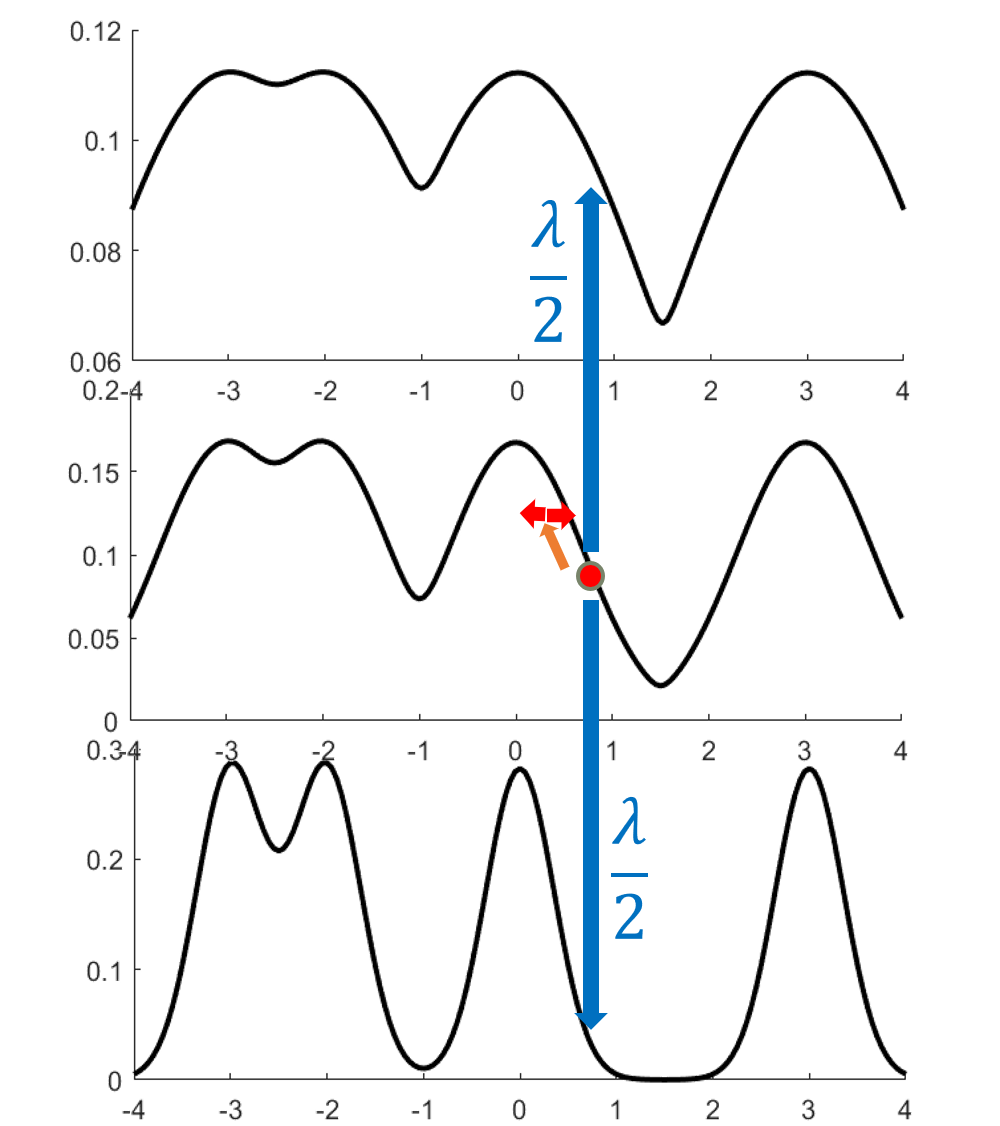

A key observation is that Langevin corresponding to a higher temperature distribution (with \(\beta f\) rather than \(f\), with inverse temperature \(\beta<1\)) mixes faster. A high temperature flattens out the distribution.3

However, we can’t simply run Langevin at a higher temperature because the stationary distribution is wrong. The idea behind simulated tempering is to combine Markov chains at different temperatures, sometimes swapping to another temperature to help lower-temperature chains explore.

We can define simulated tempering with respect to any sequence of Markov chains \(M_i\) on the same space. Think of \(M_i\) as the Markov chain corresponding to temperature \(i\), with stationary distribution \(\propto e^{-\beta f_i}\).

Then we define the simulated tempering Markov chain as follows.

It’s not too hard to see that the stationary distribution is the mixture distribution, i.e., \(p(i,x) = \rc L p_i(x)\). Simulated tempering is popular in practice along with other temperature-based methods such as simulated annealing, parallel tempering, (reverse) annealed importance sampling, and particle filters. Zheng 2003 and Woodard et al. 2009 gave decomposition results that can be used to bound mixing time; however in our setting their bound on mixing time is exponential in the number of gaussians.5

Our algorithm is the following. Assume \(\sigma=1\) for simplicity.

Take a sequence of \(\beta\)’s starting from \(1/D^2\), going up by factors of \(1+1/d\) (where \(d\) is the ambient dimension) up to 1 and run simulated tempering for Langevin on these temperatures, suitably discretized. Finally, take the samples that are at the \(L\)th temperature.

There are four main steps in the proof.

Madras and Randall’s theorem says that if a Markov chain M mixes rapidly when restricted to each set of the partition, and the “projected” Markov chain mixes rapidly, then M mixes rapidly. The formal statement is the following.

Theorem (Madras, Randall 02): For a (discrete-time) Markov chain \(M\) with stationary distribution \(p\) and a partition \(\Om = \bigsqcup_{j=1}^m A_j\) of its state space, \[\text{Gap}(M) \ge \rc 2 \text{Gap}(\ol M) \min_{1\le j\le m} (\text{Gap}(M|_{A_j})).\]

The projected chain \(\overline M\) is defined on \(\{1,\ldots, m\}\), and transition probabilities are given by average probability flows between the corresponding sets. More precisely, the probability of transitioning from \(j\) to \(k\) is as follows: pick a random point in \(A_j\), run the Markov chain for one step, and see what’s the probability of landing in \(A_k\).

This gives a potential plan for the proof. Given a mixture of \(m\) gaussians, suppose we can partition \(\mathbb R^d\) into \(m\) parts - maybe one centered around each gaussian - such that Langevin mixes rapidly inside each set. Choose the highest temperature so that Langvein mixes well on the entire space \(\R^d\) at that temperature.

Then if the projected chain also mixes rapidly, this proves the main theorem. Intuitively, the projected chain mixes rapidly because the highest temperature acts like a bridge. There is a reasonable path from any component to any other component passing through the highest temperature.

There are many issues with this approach. The primary problem is defining the partition. Our first proof followed this plan; later we found a simpler proof with better bounds, which I’ll now describe.

The insight is to work with distributions rather than sets.

There’s an idea in math that a theorem is true for sets, then it’s a special case of a theorem for functions - because sets just correspond to indicator functions.

For simulated tempering Langevin on a mixture of Gaussians, we don’t naturally have a decomposition of the state space, we do have a natural decomposition of the stationary distribution - namely the components of the mixture! Think of this as a “soft partition”.

So instead of partitioning \(\Omega\), we decompose the Markov chain and stationary distribution. We prove a new Markov chain decomposition theorem that allows us to do this.

Theorem: Let \(M_{\text{st}}\) be a simulated tempering Markov chain (with stationary distribution \(p\)) made up of Markov chains \(M_i,i\in [L]\). Suppose there is a decomposition \[M_i(x,y)=\sum_{j=1}^mw_{ij}M_{ij}(x,y)\] where \(M_{ij}\) has stationary distribution \(p_{ij}\). If each \(M_{ij}\) mixes in time \(C\) and the projected chain mixes in time \(\ol C\), then the simulated tempering chain mixes in time \(O(C(\ol C +1))\).

The projected chain is defined by \[\begin{align} L((i,j),(i,j')) &= \begin{cases} \fc{w_{i,j'}}{\chi^2_{\text{sym}}(p_{i,j}||p_{i,j'})},&i=i'\\ \fc{1}{\chi^2_{\text{sym}}(p_{i,j}||p_{i',j'}))} ,&i'=i\pm 1\\ 0,&\text{else.} \end{cases} \end{align}\]where \(\chi^2_{\text{sym}}(p||q)=\max\{\chi^2(p||q),\chi^2(q||p)\}\) is the “symmetrized” \(\chi^2\) divergence.

This theorem is where most of the magic lies, but it is also somewhat technical; see the paper for details.

We consider simulated tempering Langevin diffusion for \[ \wt p_i \propto \sumo jm w_j \ub{\exp\pa{-\fc{\be_i \ve{x-\mu_j}^2}2}}{\wt p_{ij}}. \]

The Langevin chain decomposes into Langevin on the mixture components. By the decomposition theorem, if the Markov chain with respect to these components mixes rapidly, and the Markov chain on the “projected” chain mixes rapidly, then the simulated tempering chain mixes rapidly. We verify each of the two conditions.

Thus the simulated tempering chain for \(\wt p_i\) mixes in time \(O(L^2D^2)\).

But we need mixing for simulated tempering where the temperature is outside the sum, \[ p_i \propto \pa{\sumo jm w_j \exp\pa{-\fc{\ve{x-\mu_j}^2}2}}^{\be_i}. \] This follows from mixing for \(\wt p_i\), plus the fact that the ratio \(p_i/\wt p_i\) is bounded: \(\fc{p_i}{\wt p_i}\in [w_{\min}, \rc{w_{\min}}]\). We lose a factor of \(\rc{w_{\min}^2}\). This finishes the proof of the main result.

Here are further directions and open questions we would like to explore. Feel free to get in touch if you have ideas!

Carry out average-case analysis for distributions of interest, such as posteriors of mixture models, Ising models, stochastic/censored block models, and RBM’s. These distributions are more complicated than a mixture of gaussians; for example, the posterior for gaussian mixture model is a sum of exponentially many gaussians.

One obstacle is that in many distributions \(p\) of interest, \(p\propto e^{-f}\) is not mixture of the probability distribution, but rather, \(f\) is a combination of simpler functions. In other words, \(p\propto e^{-\sum_j w_jf_j}\) rather than \(p\propto \sum_j w_j e^{-f_j}\). When this combination happens in the exponent, the decomposition approach doesn’t work so well.6

It would be great to find other uses for our simulated tempering decomposition theorem - in principle the theorem could even apply when there are exponentially many modes, as long as we create a refining partition such that there is no “bottleneck” at any point.7What are the guarantees for other temperature heuristics used in practice, such as particle filters, annealed importance sampling, and parallel tempering? One undesirable property of simulated tempering is that it incurs a factor of \(O(L^2)\) in the running time, where \(L\) is the number of levels. Particle filters and annealed importance sampling move only from higher to lower temperature, and so only incur a factor of \(O(L)\).

For example, we could consider distributions in \(\{0,1\}^d\). Here, correlation decay plays a similar role to log-concavity in \(\R^n\) in allowing a simple Markov chain, the Gibbs Markov chain, to mix rapidly.↩

The reason for the square-root scaling is that noise from Brownian motion scales as the square root of the time elapsed (the standard deviation of a sum of \(n\) iid random variables scales as \(\sqrt{n}\)).↩

Changing the temperature is just changing the scaling of the gradient step with respect to the noise.↩

This definition is stated for continuous Markov chains. By rate \(\lambda\) I mean that the time between swaps is an exponential distribution with decay \(\lambda\) (in other words, the times of the swaps forms a Poisson process). A version for discrete Markov chains is to swap with probability \(\lambda\) and to follow the current chain with probability \(1-\lambda\). Note that simulated tempering is traditionally defined for discrete Markov chains, but we will need the continuous version for our proof.↩

They proceed by first bounding the spectral gap for parallel tempering, and then showing the gap for simulated tempering is lower-bounded in terms of that. However, in our experience, directly bounding the spectral gap for simulated tempering is easier.↩

Think of the downstairs combination as an OR combination, the upstairs one as a AND.↩

We stated it in the case where we had the same partition at every level. The more general form of the theorem works even if the partitions on different. The bound could be polynomial even if there are exponentially many components.↩